|

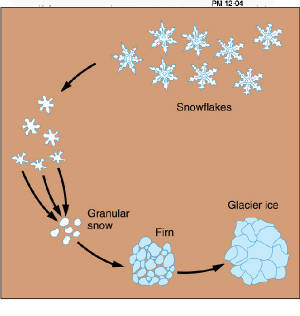

| Formation of glacial ice (Click to Enlarge) |

|

| http://www.indiana.edu/~geol116/Week11/wk11.htm |

A glacier is a large mass of ice which develops on land and is long-lasting (6). Freshly fallen snow will alternate softening

and re-freezing and eventually will compact under its own weight (4). This process continues until all trapped air is released

and the condensed snow turns into a solid glassy ice (4). The individual ice crystals are separated by extremely thin layers

of liquid water which lower their freezing point due to contained impurities (4). Along these layers of separation, the ice

crystals are able to glide ontop of eachother when subjected to the forces of gravity, which allow the ice to act in a "fluid"

manner (4). Because a glacier has a kind of liquid property to it, it will occupy the lowest ground to its flow, due

to the force of gravity (4).

Types of Glaciers on Earth

Valley Glacier

These types of glaciers are found in valleys and are usually found in areas of alpine glaciation (6). While still

growing, this type of glacier may entirely fill its valley, and eventually merge with adjacent valley glaciers (6).

Ice Sheet

Unlike valley glaciers, ice sheets are not confined to valleys, but cover

wide areas of land, of 50,000 square kilometers or more. Greenland and Antarctica are the only two places that have ice sheets

right now. (6)

Ice Caps

Ice caps are smaller than ice sheets, however, may become a widespread ice-sheet (4).

Formation and Growth of Glaciers

Freshly fallen snow consists of ice crystals with air trapped between them. Over time the snow compacts under its own

weight, and all the trapped air is expelled. Once as flakes, the snow turns into a granular form with constant thawing and

re-freezing; however, in colder climates, where the snow does not thaw, the flakes will recrystallize into finer

granules than in warmer climates. In each case, these granules merge, held together by ice, and this mass of granular ice

is called firn. (6)

Picture this! A glacier is like a slab of sedimentary rock!

Just like sedimentary rock, smaller "sediments" under pressure become fused together into one giant mass!

Did you know? Icebergs are just large chunks of glaciers that have moved into

a body of water.

| Iceberg |

|

| http://www.webtropolis.com/pub/Terry |

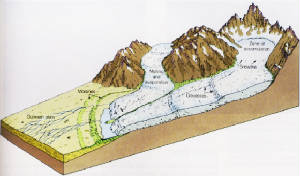

Factors affecting movement of glaciers

Although valley glaciers move under the influence of gravity, the rate of movement can vary from a few millimeters to

15 meters a day. The upper part of the glacier, which is referred to as the zone of accumulation, has a greater volume of

ice and steeper slopes. These parts of the glacier tend to move at a faster rate than the ice farther down, in the zone of

ablation (see Figure 1). In this way, ice is replenished in the zone of accumulation, where it is lost in the zone of ablation.(6)

Temperature also affects the movement of glaciers in that they tend to move faster in warmer climates where ice is

near or at its melting point, as opposed to in colder climates where the ice stays below the point of freezing. (6)

Picture this! The movement of a glacier is like the movement of stream water, where water at its freezing

point moves much slower than warmer melted water, and water near the center of the stream, as well as on the top, moves faster

than that moving along the sides and the bottom of the stream. Being on top and in the center means less resistance to rocks

and earth!

| Figure 1 (click to enlarge) |

|

| http://www.geol.umd.edu/~piccoli/100/CH14.htm |

At different points along the valley glacier, we have learned that the rate of movement is different. The upper, more

rigid, zone of ice is very brittle and therefore can be broken by tensional forces. These features shown on the surface of

glaciers, are called crevasses, and usually extend as deep as the rigid zone extends (see Figure 1, above). Crevasses

can be closed with the addition of compressive forces, when a glacier has passed a steep hill and begins to slow in speed.

(6)

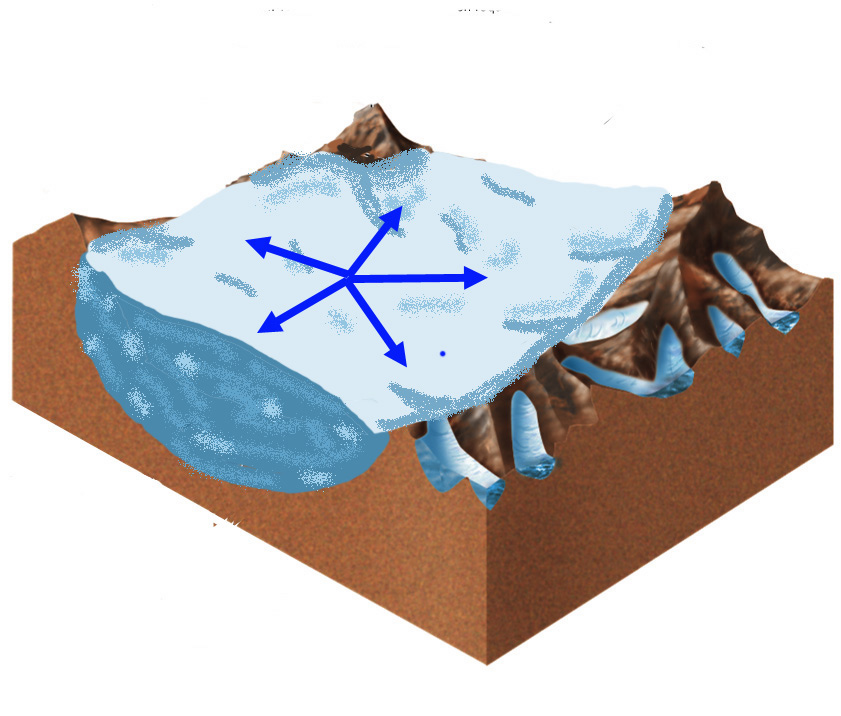

The movement of ice sheets and ice caps are similar to that of valley glaciers except that they move not along

a path, but downward and outward from a central high point toward the edges (see picture below). (6)

Did

you know? The thickest part of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is 4776 meters thick! (6)

| Movement of ice sheet |

|

| http://www.indiana.edu/~geol116/Week11/wk11.htm |

Click here for more Features produced by Glaciers

|